The following blog post is part of a series of 'Museum Showcases' which explore and celebrate collections of children's culture, education and literature across the world.

Cultural Sensitivity Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that this article contains images of deceased persons.

Denise Chapman is a practicing curator, librarian, archivist and historian with over twenty years experience in the GLAM sector. She grew up in the outback of Australia, reading comics and exploring the barren gibber plains of the Simpson Desert. Denise started at the State Library of South Australia in 2003 and began curating the CLRC in 2009, first training with emeritus curator, Valerie Sitters. In her free time, Denise keeps a large, productive garden, listens to test cricket on the wireless and volunteers to assist people experiencing homelessness in Adelaide. She is a keen student of 1940s-50s vintage dress styling and loves American Metal, Hard Rock and Power Pop of the '70s and '80s. And Rockabilly.

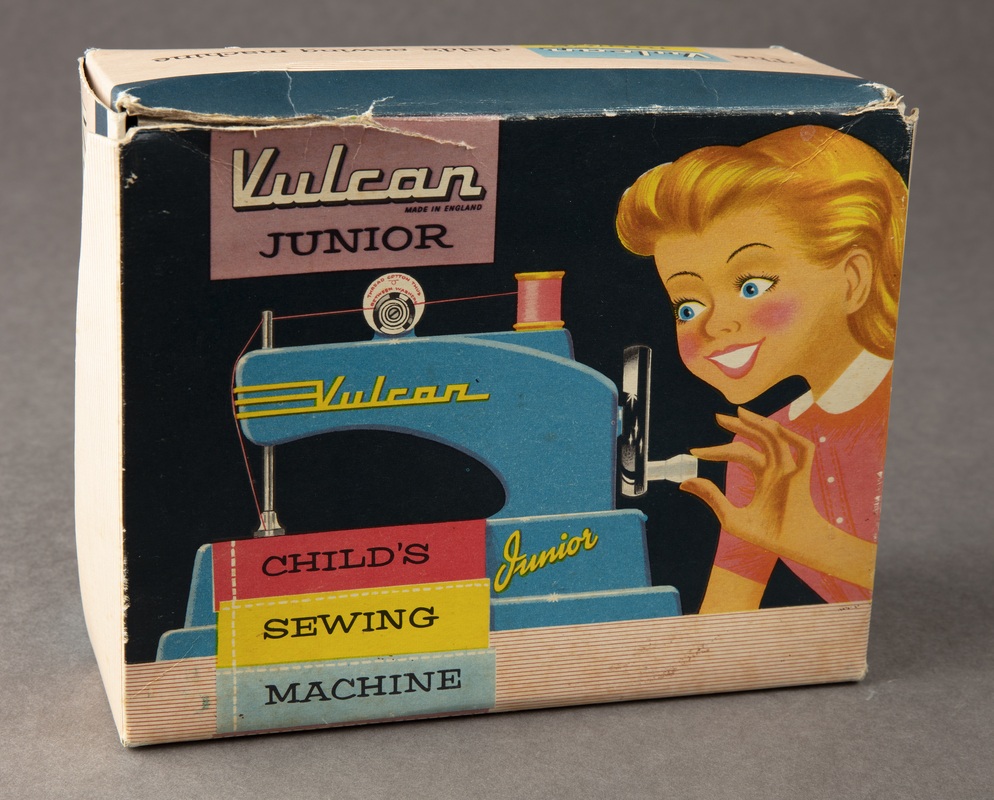

'She sews as she grows with a Vulcan’.

With these words, printed inside the boxes of the newest range of Vulcan child sewing machines in 1956-7, the English entrepreneur and manufacturer Sydney Bird reassured young mothers lining his pockets during the postwar economic boom. Here was a toy to help train a new generation of homemakers.

One ‘lucky little lady’ to receive a new brightly coloured Vulcan was Adelaide schoolgirl Chrissie Schiller.[i] Unlike many other girls her age, however, Chrissie never threaded the needle of her Vulcan. ‘So precious’ was the toy that she didn’t dare use it, instead opening and closing the box again and again to admire the machine until the cardboard began to wear with age.

Vulcan Junior Child's Sewing Machine original box, UK, 1956. The donor never used the machine as she wanted to keep it pristine but opened the box many times to admire its lovely form.

Old toys like Chrissie’s are the most sought after holdings in the Children’s Literature Research Collection (CLRC) at the State Library of South Australia. The keepsakes of children's lives, and the stories they tell, often bring scholars, individuals, the media, children and other collecting institutions into the Library’s reading room.

A research collection of over 70 years in the making, the CLRC is one of the premier heritage research collections of its kind in the southern hemisphere. Home to a significant holding of toys, games, books and ephemera spanning from the mid-1500s to current day, it belongs to a group of a dozen or so major collections of children’s culture established in Australia since the 1950s that have gone underappreciated by academics. Few beyond a small circle of scholars and librarians would recognise the acronym ‘CLRC’.

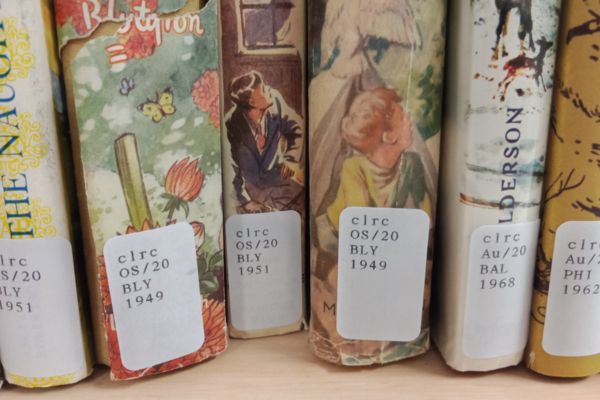

The CLRC’s toy collection is notable, but it is the published content that sets the collection apart. It was in the 1910s that the then Public Library of South Australia first developed a special interest in children’s literature and library services, later benefiting from generous public and philanthropic support. Today the CLRC is a research and reference library for the study of children’s literature of the world, particularly Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. There are comics, posters, printed games, greeting cards, paper dolls, greeting cards and school/church merit cards. The reference books and periodical sequences include published books, bibliographies, indexes, periodicals and other materials about children's literature.

The CLRC itself has a complex and chequered history, oscillating in and out of organisational favour. The entire collection was always on display during the 1970s, 80s and 90s, and boasted a team of staff. Now it is securely stored, attracting the ire of some sentimental stakeholders who perceive changes to storage and handling practices (e.g. mediated access to the artefacts) as institutional negligence rather than the application of curatorial rigor. In truth the greatest obstacle to the CLRC’s accessibility has been the failure to address the cataloguing of the books collection with the advent of electronic retrieval systems (too big, too hard, too costly), a decision that has become the collections’ most questionable legacy.

But change is on the horizon. With curatorial advocacy, a responsible executive and a supportive Libraries Board all converging, funding was secured in 2019 to catalogue the vast collection of non-Australian children's literature. With over 50,000 books from the nineteenth and twentieth century, this is no small undertaking. Fortunately, all the Australian material, plus the 900 toys/realia and almost 900 games, are already described on the online catalogue and any new purchases or donations are now catalogued as a matter of course.

How does an historic children’s literature collection come to hold so many artefacts?

The State Library of South Australia first started collecting toys for the CLRC in the 1960s when descendants of South Australian colonial families wanted to donate the artefacts of their childhood with their literature. Along with skittles and games came figurines, greeting cards, school exercise books, merit certificates and other keepsakes.

The Gilbert Family, pastoralists and vignerons of Pewsey Vale in South Australia’s Eden Valley, donated many toys, games, books and realia with their family archive. Notable is Henry Gilbert’s collection of bird’s eggs, begun in 1886, and for which he received First Prize in the Collection of Sundries category at the Williamstown exhibition of 1888, aged 8. His collection predates the Gould League of Bird Lovers, a bird protection organisation established in Victoria in 1909, which later helped spark a major shift in attitudes towards egg collecting in Australia. Henry later studied medicine in London and went on to private practice in Adelaide. We can view his career through the prism of his childhood interest in science and nature as well as his collection of books on astronomy.

Bird’s eggs, collected by Henry Gilbert, 1886.

Henry Gilbert's certificate he received for his entry of the eggs in a local country show exhibit, 1888.

Curious tidbit from the curator

As most libraries are constructed to store books, storage of the material culture is always an issue. This image shows part of the storage system for the 181 boxes of 900 toys. The boxes are not in numerical order, rather they are placed where they fit, so a map was created for ease of location (seen hanging off compactus in middle of image). With little space remaining, judicious collecting of objects with a useful backstory has become essential.

The Literature sequences

The CLRC’s books collection is vast at over 75,000 holdings. It is an international collection with a strong British and American influence, although there is a sizable collection of foreign language books and Australian classics published in German, Italian, Korean and Arabic. Australian children’s literature is represented from its earliest beginnings with Charlotte Barton’s A Mother’s Offering to Her Children (1841) to the present day.

The collection is significant as it contains aesthetic appeal and preserves comprehensive bodies of work by practitioner artists of the ‘Golden Age’ of children’s book illustration (e.g. Walter Crane, Beatrix Potter, Edmond Dulac, Arthur Rackham et. al). There are also examples of hand-coloured illustrating and chromolithography as well as a huge range of modern artistic techniques and media such as collage, elaborate fly leaf illustration, hand-crafted and machine-generated moveable formats. Rare imprints, variant editions, publications with errors and other eclectica add to the significance of the collection.

One treasure among the nineteenth-century children’s books is contained in the Unitarian Church Children’s Library (UCCL) as a discrete sequence within the CLRC. The Library was established in Adelaide in 1859 by ladies of the Church in the hope of exciting a taste for reading among the younger members of the congregation, creating a lifelong bond with the church and guiding moral tendency by combining amusement with instruction. The UCCL closed in 1969 and in 1990 the Library of 700 books was donated to the CLRC by Audrey Abbie, a former librarian of the UCCL who preserved the collection in her home when it was no longer in use. The UCCL provides a rare glimpse into the functioning of a nineteenth-century children's library.

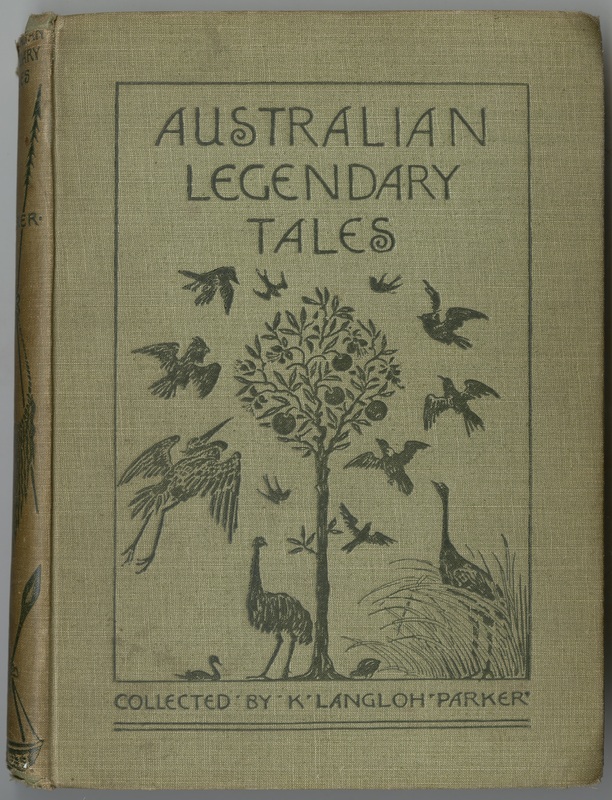

The books collection also reflects changes in cultural attitudes towards Aboriginal people in Australian children’s literature. It can be used to trace the transition of books about Aboriginal people by non-Aboriginal authors for children of colonising families, to books by Aboriginal people about and for Aboriginal children being created in language and published by Aboriginal controlled publishing houses (e.g. Magabala Books).

Catherine (Katie) Langloh Parker (1856 – 1940) is best known for recording the history and stories of the Euahlayi/Noongahburrah people in north-western New South Wales. She published Australian Legendary Tales (1896) with an introduction by folklorist Andrew Lang. While it is unclear whether the book was intended for children, it was generally accepted as such. The tales were well received and went into a second edition with More Australian Legendary Tales (1898). Parker’s works are controversial for the disclosure of sacred knowledge though they have also been used by Aboriginal people to reconnect with their heritage.

Collection Development

The CLRC once had a reputation for collecting the good, the bad and the ugly as a broad representation of reading material created for children. Lately, however, storage tensions and changes in collecting priorities have facilitated a more strategic acquisition policy. The growth of the self-publishing industry has resulted in a tidal wave of material that cannot be comprehensively collected by the CLRC. Fortunately there are other obliged holding libraries to cater for each states’ output (e.g. Legal Deposit) which ensures all published material in Australia is discoverable.

The annual book purchasing budget for the CLRC has been exceedingly small since the collection went into storage nearly 20 years ago, limiting purchases to the Children’s Book Council of Australia Book of the Year awards shortlist only. This was sidestepped by collaborating with judges in the different categories who donated the books they assessed. In recent years a larger budget allocation and access to other funds has seen an uptick in the range of books collected.

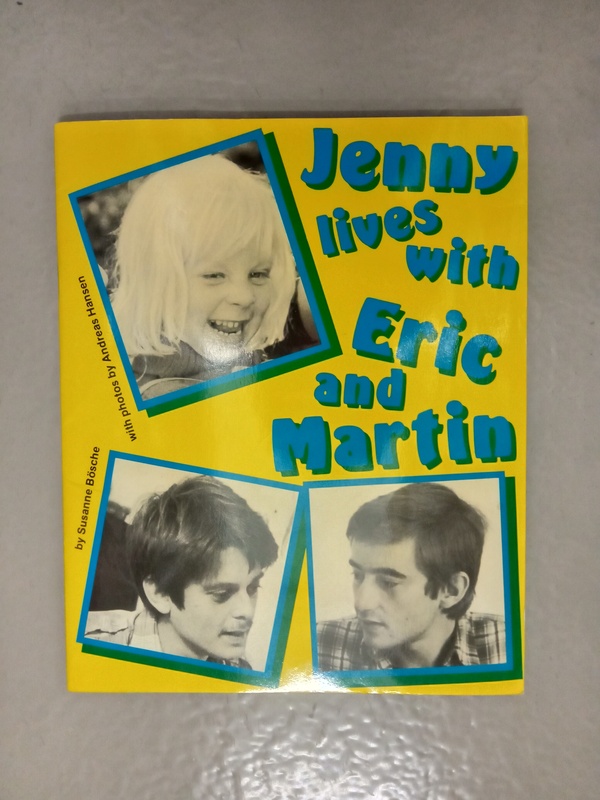

Efforts are currently being made to acquire more controversial books (e.g. David Walliams’ The boy in the dress (2013)) and enigmatic publications sought after by scholars. For example, Susanne Bösche’s Jenny lives with Eric and Martin (1983 [1987]) was purchased a few months ago for a pretty penny after a ten-year hunt. It is the first known (modern era) English-language children’s book about gay men living together in a parenting role with the child as the protagonist. The narrative uses a photo-story technique and chalk drawings to convey the messages. It was strangely absent from a collection of historic children’s literature curated by a jet-setting completist, at the time the book was published.

Games Collection

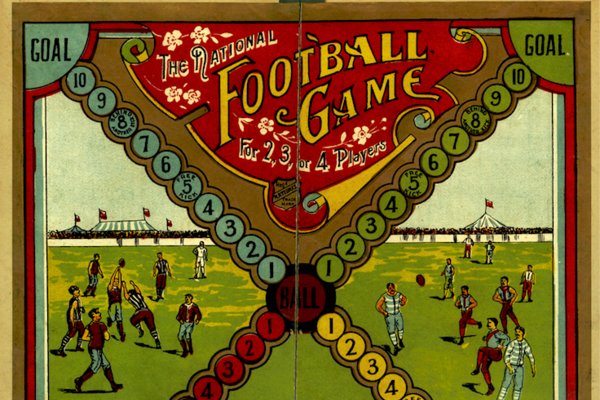

The board games page on the SLSA’s ‘SA Memory’ website explains something of the games held by the Library. The generous collection of ‘National’ games is the most distinctive feature of the CLRC games collection. The National Game Company, established by W. Owen in Ballarat, Victoria, at the beginning of the twentieth century, is believed to have been the first large scale manufacturer of board games in Australia. Many of the original watercolours created for the games were designed by English-born Christopher George King, a talented illustrator and artist who worked for the National Games for over 30 years. (He died in 1928 at the age of 63.)

The National Football Game, Melbourne, National Game Co., ca. 1910, illustrated by Christopher George King.

National Game Company Lithographed Printer’s Proof, 1904, one of a set of four proofs measuring 107cm x 77cm.

One of the most aesthetically curious and rare items from the Company is a National Game Company Lithographed Printer’s Proof for board games and boxes from 1904. The CLRC’s games collection holds many of the published games for the elements shown on this sheet, which has used the space to maximum advantage.

Another notable acquisition are the board games in the James Hardie Childhood Collection (JHCC). Once the nucleus of the Australian Museum of Childhood, the Hardie Collection was part of a larger collection of children’s artefacts, book illustrations and games that were dispersed into several different major collecting institutions by the National Trust of New South Wales after the Museum closed in 1996.

One of the oldest parlour games in the Library is believed to be the Fishponds game, published in 1856 by Alfred Seeley. This also belonged to the children of the Gilbert Family. It is very hard to hook a fish, especially in front of an audience of young children!

Fishponds is one of the oldest parlour games in the Library's collection, 1856. This game is more complicated and more difficult than the modern fishing game played with magnets. Fishponds has a hook on the end of the string attached to the rod and it requires considerable deftness of touch to 'hook' a fish!

Of all the visual formats in the CLRC, the games collections contains some of the most notorious and sensitive material. There are several games based on gambling and the horse-racing industry such as the betting game 'Totopoly' (Sydney, John Sands, 196-?) and 'Casino Vegas' (n.p., John Sands, 1975) which contain a roulette wheel, blackjack cards and play paper money. There are also cigarette cards which were collected by children who purchased the cheap cigarettes for the cards and often also smoked the cigarettes. These all have an obvious ‘grooming’ nature to them and always raise an eyebrow when on display.

‘The game of Blackfellow‘ (ca. 1900 – 1920?) is one of the most confronting and revealing games in the collection. The object of the ‘game’ is to use tokens of armed police on foot, and mounted, to chase Australian Aboriginal people. It is a most complacent interpretation of a violent subject-matter created by the ‘hare-brained’ ‘no-talent’ journalist, Reginald Carrington.[ii] Some of the card games also feature pictures and descriptions of First Nations people of Australia and the Pacific regions which would make your toes curl.

Collection highlights

A beautiful ‘role-playing’ toy, this Mettoy Tin-plate typewriter has a painted keyboard, letter-selector dial, and paper feed. Great Britain, 1950s. Donor unknown.

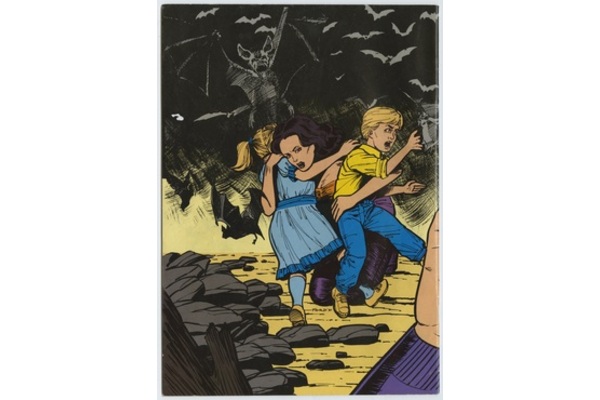

Phantom Comic, The Wings of Death, 1991, back cover used as exhibition dressing for the Creepy Bay of the Play exhibition, 2017. Not catalogued.

German Bisque Doll, ‘Elizabeth’ [1910?]. This much-loved doll has the hair of the girl who played with her during the 1940s and had belonged to the girl’s mother as a child. Bespoke clothing and accessories were made for Elizabeth. She was also ‘operated on’ to remove her appendix and a lump on the brain. Not surprising given the donor’s father had been a GP.

A difficult-to-research piece. ‘Six in the bed’ Thuringia lidded porcelain lidded trinket box manufactured by Ernst Bohne & Sons, Germany. ca.1885. 7 x 7 cms.

Soon to launch on our Stories web page is a category for ‘curious’ objects held at the Library. In 2022 we will publish an article about some Thuringia porcelain in the CLRC collection over which there has been much speculation, but mostly unease, as almost everyone finds this design motif creepy.

When he was donated in 2019, Keiffee the koala was very clapped out. He came with family photographs, his own scarf and the lovely memories of the lady who played with him as a child, just after the Second World War. Keiffee has since gone viral with young and older folks, especially regional early learners who became obsessed with him during the digital visits presented by the Library’s education team during 2021. Read the story of this handsome fellow and his revivification on the State Library’s Stories page @ Meet Keiffee the post-war koala toy. (Keiffee the Koala came dangerously close to defining the curator’s career.)

This painted Noah's ark was made in England by soldiers wounded during the First World War, at a factory known as the 'War Relief Toy Works' which was based in Stoke Newington, London. Alas, this toy lacks the carved wooden animal figures, and those of Mr and Mrs Noah, which would have made up the set. Noah’s ark was the most common toy produced by the War Relief Toy Work factory. This piece was salvaged from the partial demolition of an Adelaide school 20 years ago, by a retired teacher who donated it during 2020.

A curator favourite: Wooden Noah’s Ark toy, UK War Relief Toy Works, ca. 1920. See Story @ The tale of an ark, a wounded soldier and an Adelaide School.

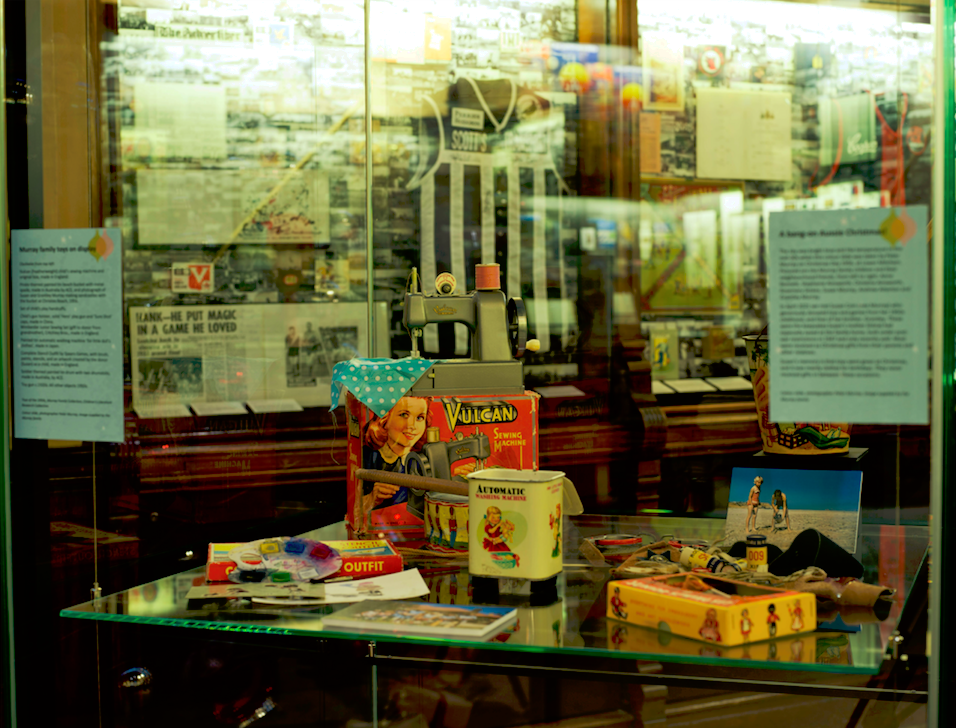

A recent acquisition of childhood artefacts. The Murray Family Collection of toys received as Christmas gifts during the mid-1950s. This display was placed next to the giant Christmas tree for Christmas at the Mortlock, 2021. Toys featured are a miniature washing machine for dolls clothes, a stencil set, sewing machine, tin drum and sticks, toy gun, holster, caps and handcuffs, a tin beach bucket and spade and a junior sewing kit. Family photographs completed the story.

Children’s voices

In recent years a number of historians have journeyed to South Australia in search of the records written and authored by children. Although the CLRC itself focuses on material culture and published content made for children, child-authored material can be discovered within the Library’s other collections.

Indeed, several important anthropological collections are held at the Library. There are, for example, Aboriginal children’s crayon drawings from the 1940s held in the Mountford-Sheard anthropological collection, the John Morley collection of 28,000 children’s drawings (1965-1975) which includes works by children with different degrees of intellectual disability, and the drawings of Aboriginal children in the Top End collected by school teacher and puppeteer William Dalziel Nicol (in process, PRG 1267).

This set of pencil and watercolour drawings (Child’s sketchbook and artworks, late 19th century), was discovered in a drawer of CLRC posters a few years ago, unsettling a number of Library staff and researchers.

Aboriginal children from Ernabella, playing on a swing attached to a tree. A ladder is propped against the tree for climbing, Mountford-Sheard Collection, 1940, PRG/34/1264B. The State Library has permission to reproduce this image from community advocates at Ara Iritija.

Unknown child artist, ca. 1880-1885, depicting what appears to be cats ascending to Heaven, accompanied by angels, with three children standing in the foreground. Worse still are the drawings of drownings, a child in a cage, a haunting, goblins, a house fire, and Lear-like other-worldly characters contained in this set, which can be accessed online.

The Library also holds hundreds of photographs of children engaging in learning activities and play, many of which have been released online and can be explored via the catalogue. More recently the Library has been collecting media, including children’s responses to COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, during a campaign entitled Remember my story.

Like Australia’s seven other state libraries, the Library has significant collections of oral histories as well as unpublished and published childhood reminiscences. The Reminiscences of the Cameron Family (D 7249) are one example of what can be found in cultural collections which record childhood experiences and activities. The Cameron children had many heavy chores, however, Tom Cameron (1861 – 1952) recalled that during playtime as a child in the 1870s

... we used to make up our own theatre. We had figures on sticks, and three of us operated those from the sides of a homemade stage. The whole thing was about as big as a table, while another lad behind the curtains read the dialogue. It was good fun and we used to charge our friends a penny to see it, and then of course we used to have our own concerts and I think there was more home life in those days.

Tom also speaks about smoking from about age ten, and how he and his friends spent most of their pocket money on tobacco for their pipes!

I had one of those!

As the curator of the CLRC I have sometimes been overwhelmed by how engaged the community is with the collection and its future. The recent revivification of the status of the CLRC has given the community new confidence in the Library’s stewardship of their ancestor’s objects, and in the care their donations will receive. The most wonderful moments for me have been seeing the reaction of people to items from the collection, especially in exhibitions. The Library’s ‘A Theatre Inside the Book’ exhibition (2015-16) of paper engineering from the CLRC was hugely popular. It was subsequently followed by the exhibition, ‘Play’ (2017), which appealed to a broad demographic and from which many programs were developed and are still used. We’ve had tears of joy, wide-eyed stares, gasps and even people saying they ‘feel funny’ when they see a display of long forgotten-about books, toys and games.

One of the few redeeming features of all adults is that they have once been a child, and the poignancy of their recollections of joy and wonder seem universal, no matter how fleeting they may have been in their childhoods.

[i] The donor’s name has been altered to protect their identity at their request.

[ii] Peter Morton, Lusting for London: Australian Expatriate Writers at the Hub of Empire, 1870-1950, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, p 109.

Written by Denise Chapman, Curator – Engagement, Engagement and Marketing Team, State Library of South Australia ([email protected])

Edited by Emily Gallagher, CHS Digital Media Officer

Further Reading

Some links to other recent stories and new products based on CLRC holdings:

- Don’t touch that dial! Children’s radio club badges and pins

- United in Victory

- A visit from Father Christmas

- Make your own Spitfire and Bomber Squadron

- Raphael Tuck face masks – Which character will you be?

Click on these links for an overview of the CLRC material that has been digitised and interpreted to date: