Tasked with finding ways of bringing PGRs and ECRs together from the Children's History Society and the History of Education Society (UK), the Education and Children's Histories group formed in 2021, organised by PGRs Catherine Holloway and Ellie Simpson of the University of Winchester, UK and Catherine Freeman of University of Greenwich, UK. After a series of online writing retreats, ECH hosted an online international conference in October 2021.

To continue the conversation in 2022, Catherine Freeman invited PGRs and ECRs working in children's and education histories to find an image that had resonated with them in their research and present it with five Tweets explaining its importance. The resulting Tweets published on @EducationChild4 illustrated the breadth of enquiry across the two societies and are presented here.

Hounds Lane School

By Ruth Felstead (Newman University)

Hounds Lane School, Worcester, 1967, just before its demolition. West of the city and River Severn in the background. Worcester’s only city board school, the building was eventually demolished in the 1960s to make way for a Ring Road.

Credit: cfow.org.uk (Clive and Malcolm Haynes)

The school, built by the Worcester School Board and opened in 1873, was impressive; winning acclaim for its ‘admirable’ classrooms and hot air heating. Close to the river, it dominated the district known as Birdport, yet its pupils were amongst the poorest in Worcester.

Logbooks are lost or destroyed. Other materials show: many children left at 10 with a ‘Dunce’s’ Certificate; the WSB believed in educating pupils for their future life; in 1889 they refused to buy a piano as it might mean children getting ideas above their station.

Severe misbehaviour could risk boys being sent to a training ship, HMS Formidable, near Portishead, to learn seamanship. Often, they would eventually join the Navy. Other children including girls were sent abroad to the Empire, sometimes with parents agreement.

Patriotism was deemed important, and the school song was sung to the tune of ‘God Save the Queen’. Boys learned to drill with dummy rifles and the school was presented with a Union Jack flag by the Navy League in 1900.

Good morals were seen as essential for children’s adult life: “Habits of order, obedience and thrift, inculcated in childhood, are not without effect upon the mature life” Quote from the Board’s valedictory statement in 1903. After this, the school was run by the county council.

Ruth Felstead is a PhD Student at Newman University, UK. Her thesis topic is 'Moral, patriotic and imperial values in Birmingham and Worcestershire elementary schools 1880-1902'. You can follow her on twitter at @RuthFelstead.

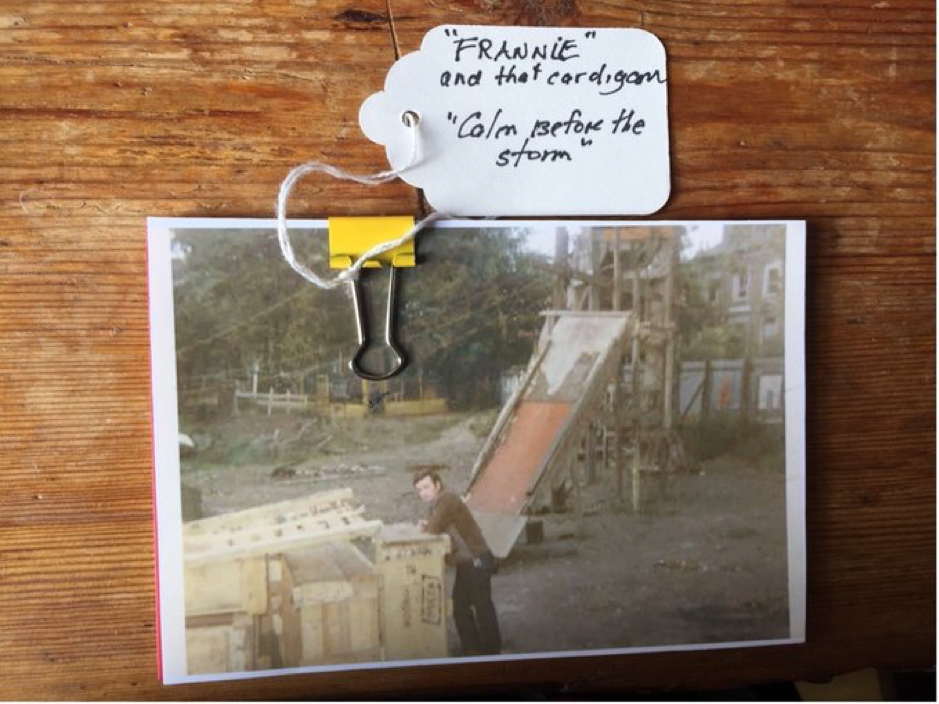

Calm Before the Storm

By Emily Baker (University of Greenwich)

Man standing in derelict playground with slides and wood panelling around him. Note on the picture says “Frannie and that cardigan” “Calm before the storm”

Credit: Grove Adventure Playground, undated.

During my research concentrating on migrant children’s memories of play, I discovered the Grove Adventure Playground in Brixton and some of the history behind this play space. The playground was originally called Angell Town Adventure Playground and was opened in the 1969.

“Frannie” in this photo was the original playworker is Francis McLennan, the UK’s first ever trained play warden, is waiting at the playground. The playground and its fixtures are much bigger than him. I like that the playground is obviously bigger than the playworker.

Francis ardently advocated for the adventure playground. During Frannie’s time as an active advocate and supporter for young people in the area, the government instituted the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, 1984 which gave them the right to stop and search young people.

The comment on the photo about the calm before the storm speaks to more than just the arrival of children and young people, it can also be used as a reference to the development of policies that deteriorated relations between the government and many young people.

The migrant children I spoke to emphasised the importance of safe play spaces like the Angell Town Adventure Playground. Migrant children's existence embodied a politicisation within 20thC Britain. Their play experiences help show the impact of migration in their lives.

Emily Barker is a PhD Student at University of Greenwich, UK. Her thesis is on 'Memories of migrant children’s play in Britain 1970 – 2000 with a special focus on play patterns’ reflection of migrant experiences'. You can follow her at @barkflo.

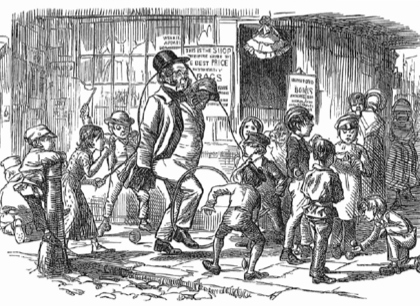

Poor Playgrounds

By Jon Winder (University of London)

Poor Playgrounds, Punch, 4 June 1859, p. 233.

In attempting to uncover the roots of public play spaces for children, I discovered this image and accompanying article from Punch in 1859, promoting the need for dedicated public spaces for play.

In the 1840s, schools such as the Home & Colonial Infant School in Gray’s Inn Lane, London, had space for energetic outdoor recreation but few public spaces included specific facilities for children.

Pioneering public parks in Salford and Manchester did include segregated gymnastic equipment for girls and boys but in general landscape aesthetics trumped play provision in early city parks.

By the mid-19th century, there were high profile calls for the provision of public places to play & a Playground & Recreation Society was established in London.

However, despite high profile supporters, including Charles Dickens and the editor of Punch, the Society had folded within a few years. It would be another 3 decades before public playgrounds became a more regular feature of the urban environment.

Jon Winder is a researcher at the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London. His PhD thesis was on the history of public play spaces for children in Britain. You can find him on Twitter at @jonwinder_

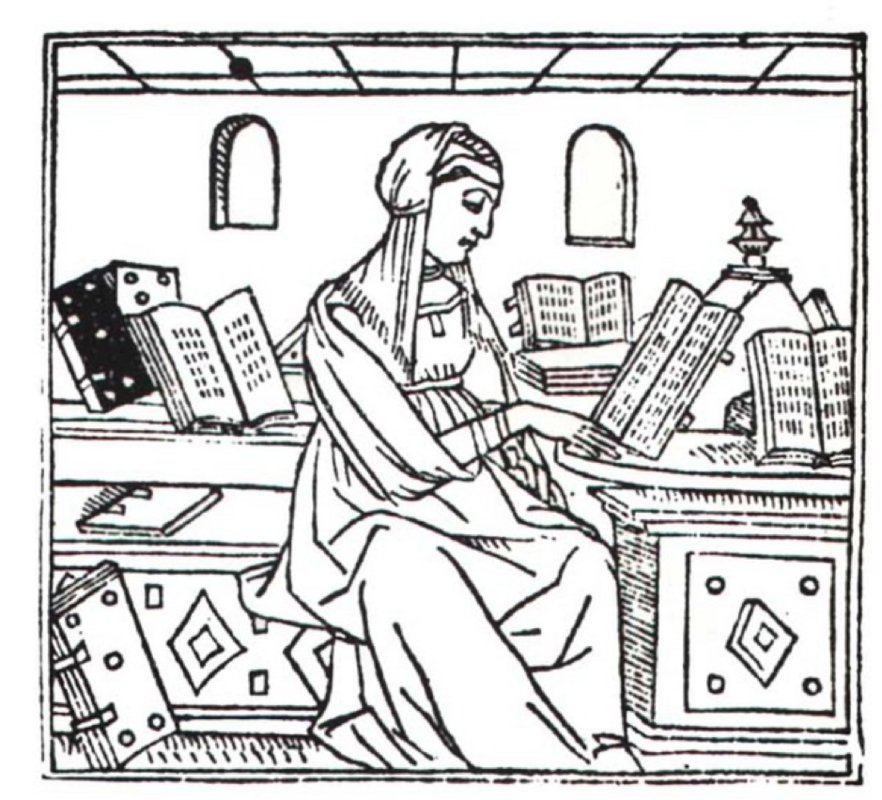

Isotta Nogarola

By Elena Rossi (University of Oxford)

A woodcut of Isotta Nogarola (1416-1466) reading in her house and surround by books. Produced in 1497 to accompany details of her life in Giacomo Filippo Foresti’s ‘De plurimis claris selectisque mulieribus’.

Isotta Nogarola was an Italian intellectual based in Verona. After her father’s death, her mother, Bianca Borromeo, hired Martino Rissoni to tutor Isotta and her sister. Rissoni was a student of the renowned humanist Guraino Veronese and provided important connections.

As was typical in humanist circles, Isotta began corresponding with many scholars through letter writing. However, Isotta was soon attacked for her intellectual pursuits. An anonymous writer accused her of being unchaste and incestuous as ‘an eloquent woman is never chaste’.

Resultantly, Isotta chose to live an isolated life dedicated to religious studies. She started a correspondence with the nobleman and Venetian governor, Ludovico Foscarini. Together they wrote ‘Dialogue on the Equal or Unequal Sin of Adam and Eve’.

This image of Isotta is particularly interesting for my research as it shows the legacy and rising significance of female intellectuals. The woodcut was created 30 years after her death and included in a catalogue of famous women, setting an example for women’s education.

Late-medieval Italy saw a rise in educated women, who were not always respected within society, but by the end of the 15th century these ladies were being celebrated. Despite various obstacles, Isotta was dedicated to her studies, which is embodied and immortalised in this image.

Elena Rossi is a PhD Student at the University of Oxford, UK. Her thesis is on 'How women encountered worlds of learning in the university towns of Oxford, Paris and Bologna c. 1270-1500'. You can follow her on Twitter at @elenafranrossi.

From the Front

By Jade Ryles (University of Adelaide)

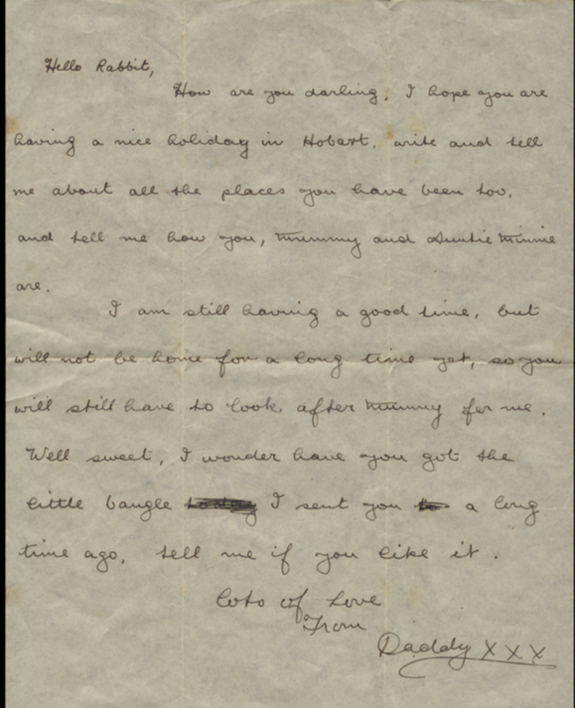

Letter from Captain John Stirling to his daughter Jean Stirling (undated, estimated to be between 1940-1942).

Credit: Australian War Memorial, AWM2022.6.163

During my research on Australian children and their servicemen fathers, I came across this letter written by Captain John Stirling. This letter is one of 28 letters written to his daughter Jean Stirling throughout his time in the 2/40 Australian Infantry Battalion. Unfortunately, Jean’s letters and replies no longer exist.

John Stirling’s letter is just one example of how fathers and children communicated during the war. The letter clearly demonstrates a loving relationship between John and Jean – but when placed in the broader context, it demonstrates the constraints of letter-writing as a form of communication between fathers and children.

For example, both government censorship and self-censorship made it difficult for fathers to produce letters with interesting content, or content that accurately depicted their experiences. John was most likely not “having a good time”, but to go into any detail would be breaching censorship guidelines.

The letter was also useful to my research as it demonstrates the emotional burden placed on children during the war. John asks Jean to look after her mother, a difficult task for a girl of no more than 6 or 7 years of age, but a sentiment that was echoed by fathers to their children across the majority of letters that I encountered.

John and Jean’s story has an unfortunate end. One of the final letters in the collection is unfinished and followed by a telegram notifying John’s wife of his death. John’s letters stood out to me as they were the first collection of fathers’ letters that I read in which the writer did not survive.

Jade Ryles is a postgraduate student at the University of Adelaide, Australia. Her thesis is on 'The impact of the Second World War on the relationship between Australian children and their servicemen fathers'. You can follow her on Twitter at @RylesJade.

Secret Garden

By Catherine Freeman (University of Greenwich)

Gateway to Princess Mary Village Homes, languishing in the garden of Chertsey Museum, Surrey.

Credit: C. Freeman, 2016.

Researching girls’ education & employment in the English county of Surrey, 1870 to 1914, I found a girls’ industrial school, the Princess Mary Village Homes for Little Girls, founded in 1870 by Mrs Meredith. Run on the Family System, girls lived in purpose built cottages.

Built on fields in Addlestone, cottages were overseen by employed ‘Mothers’, to teach girls how to live in an ideal family. The school had a shop, hospital, chapel and gardens to complete the village, along with industrial laundries and bakeries for industrial schooling.

Initially Mrs Meredith educated girls for domestic service. By 1900, employment routes had expanded & girls had gone to be teachers, nurses, Post Office clerks as well. The school had a Girl Guide troupe and the local fire officers trained an in-house fire brigade.

From a restricted initial stance, Mrs Meredith’s pedagogy and philosophy developed & so did the school, curriculum & girls’ lives.

Unexpectedly finding this arch when visiting photo archives was a poignant moment, bringing me closer to the girls’ whose stories I was unfurling.

The site became a housing estate in the 1980s. This is a hidden reminder of girls’ industrial schooling.

Catherine Freeman is a PhD Student at the University of Greenwich, UK. Her thesis is a study of girls' education and employment, 1870-1914. You can follow her on Twitter at: @CatGQFreeman.